The Long-Term Debt Cycle

By Alon Ozer, Chief Investment Officer, Omnia Family Wealth

In biblical times, the jubilee year is the year that ends with seven cycles of “shmita” (release) which occurs every seven years. The fiftieth year is special in many ways, but what’s relevant to this memo is that on this year, debt that was due before the jubilee year is forgiven.

Thousands of years ago, people figured that at some point high debt levels can’t be rolled over and something has to be done to give the economy a kick start. The big question today is how close are we to an end of the long credit cycle?

Since the global financial crises (GFC) in 2008, central banks around the world provided massive liquidity using different measures to support the economy. Since 2015 and until January this year, it was clear that the direction the central banks are heading in is monetary tightening, started by the Fed and to follow by the ECB. But market behavior last December was an eye opener for many investors and central banks, and the direction they were headed is now in question. Many investors including the Fed now wonder, if the market can’t take a 25-basis-points-hike in interest rate, what is the true condition of the US economy?

The hint for a shift in policy came very quickly; in its January 30 meeting, the Fed said it would be “patient” about increasing rates further, hinting no additional hikes are likely this year.

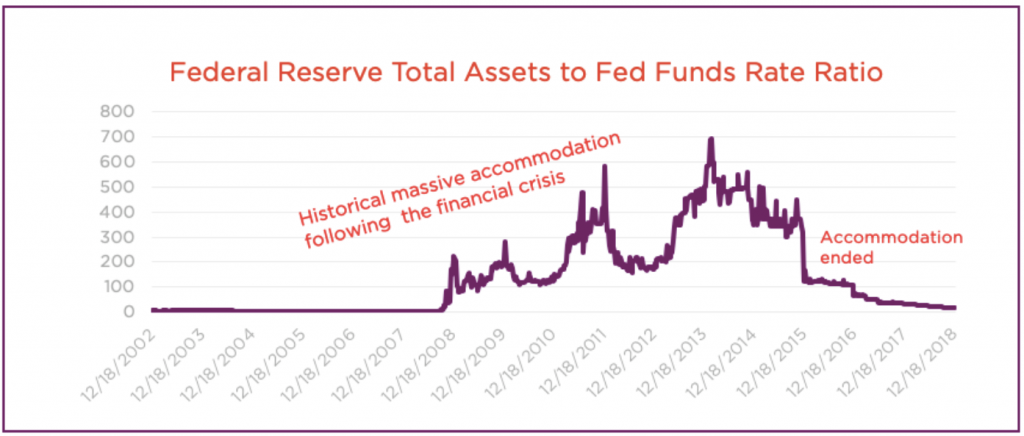

Source: FRED

TIGHTER MONETARY POLICY

Current tightening actions are much more aggressive than in past tightening cycles, the combination of rising interest rates, tax cuts, much higher government spending and the elimination of $50 billion from the Fed’s balance sheet monthly, will remove trillions of dollars from financial markets in the next few years, if continued.

The chart above is a ratio of the Fed balance sheet and the Fed funds rate. It shows us the level of accommodation through lower interest rates and financial assets purchases. In 2008 and until 2014, the Fed provided a massive accommodation through both lowering and keeping interest rates close to zero and purchasing financial assets. Today, this ratio is still higher than normal but significantly lower than in the last couple of years.

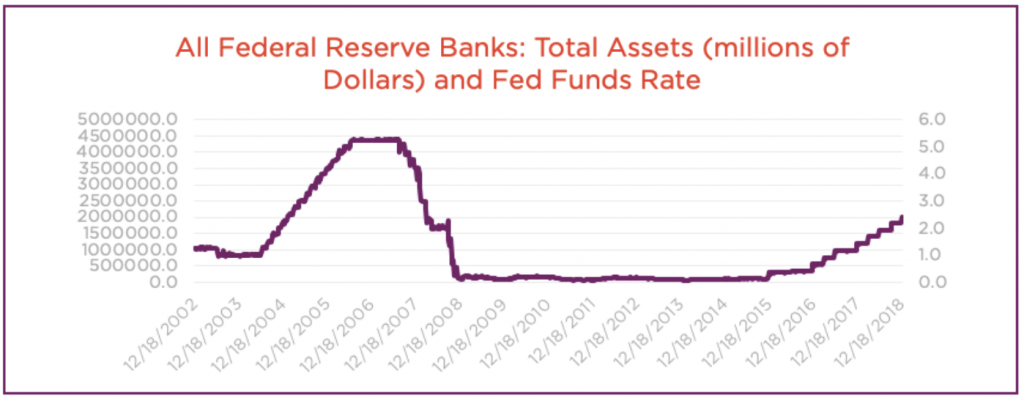

Starting in 2008, the FED created 3.5 trillion dollars to pull the world economy out of a potential multi-year depression. They created the money by making deposits in the accounts of commercial banks held with the Fed (required reserves). This is not a new tool for the Fed and one of the main tools they used to control interest rates by changing banks required reserves. Back in 1936 for example, to prevent an “injurious credit expansion,” Fed policymakers doubled reserve requirement ratios to soak up banks’ excess (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis 1936).

Today this tool is not as effective if at all. Due to the large deposits the Fed made in past years, the banks now have much higher reserves, so small withdrawals/increase in required reserves will not be sufficient. This is actually the reason the Fed started paying interest on banks deposits, something they weren’t able to do before 2008, and by that effectively raising the short-term interest rate-fed funds rate.

We think this is one reason the Fed is not in a rush or need to “normalize” the size of its balance sheet to control short-term interest rates (by effecting commercial banks’ reserves), all the Fed has to do is change the interest rate payed on the reserves. (Banks will not lend at a rate lower than the rate the Fed pays for theirs reserves.)

INTEREST RATE CHALLENGE

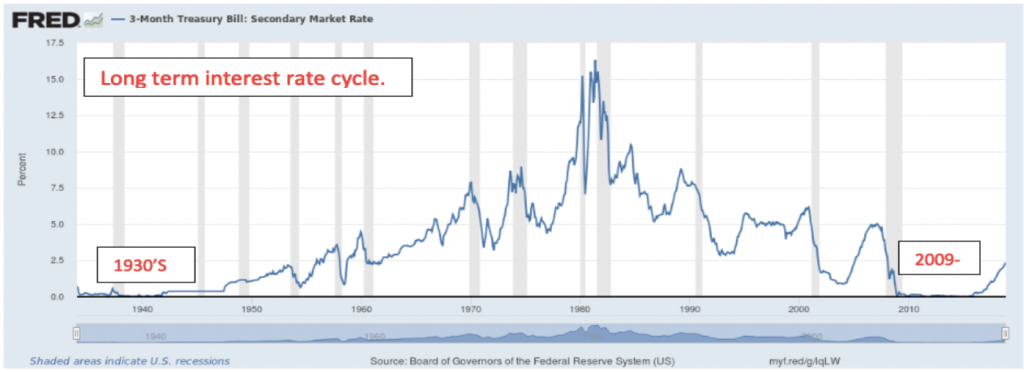

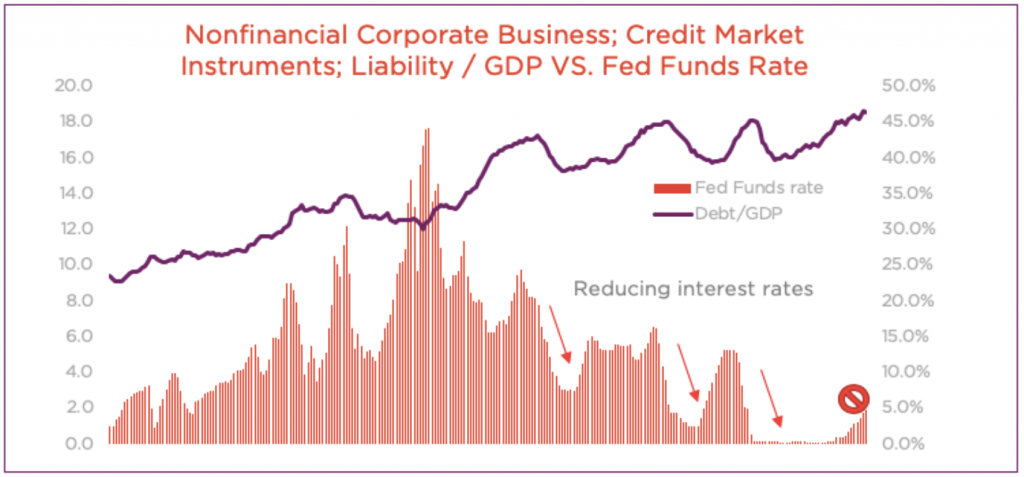

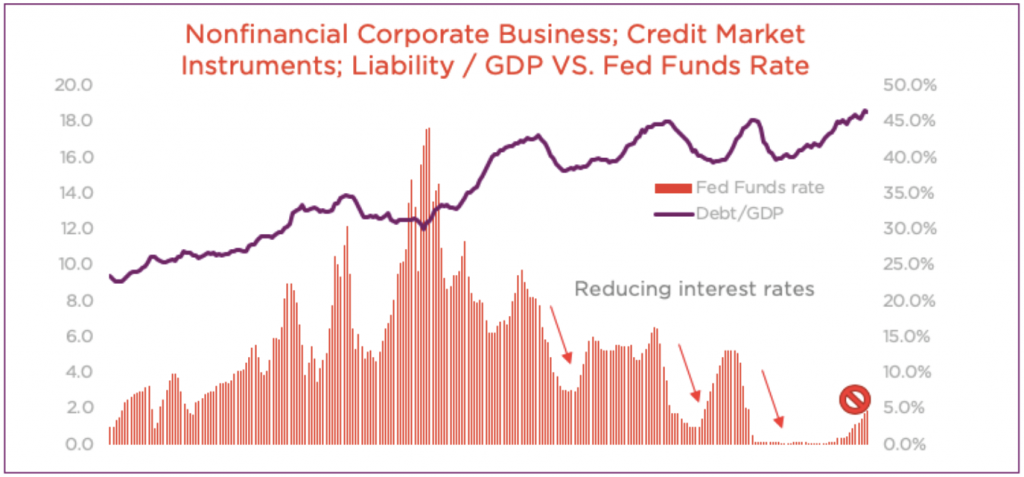

Dealing with the last five recessions (short-term debt cycles) the Federal Reserve Bank lowered interest rates by 400-500 basis points to stimulate the economy, making it easier for borrowers to roll their debt and making taking new loans more attractive. In more severe recessions, they also printed money and purchased financial assets.

At current interest rate levels, this important tool will not be available or efficient as in last recessions. Zero, or close to zero, interest rate is a very challenging place to be in for an economy and a central bank. This situation is new for today’s central bankers; they have not faced this situation before. (The closest time was back in the 1930’s.) It’s only the second time in almost 90 years that the Fed is in tightening mode after interest rates hit zero levels. If the Fed continues with tightening, we could see an end of the long-term debt cycle.

Source: FRED, Omnia Family Wealth

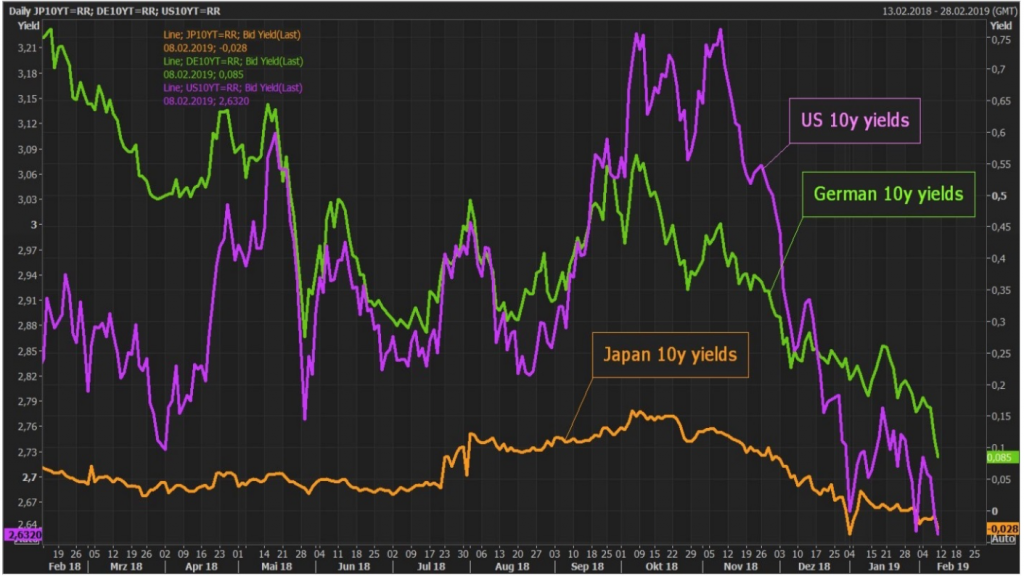

Looking outside of the US, some central banks still hold interest rates at negative territory. Like the ECB for example, if the EU is heading into a recession with still negative interest rates (and no QE), the markets will face a significant challenge.

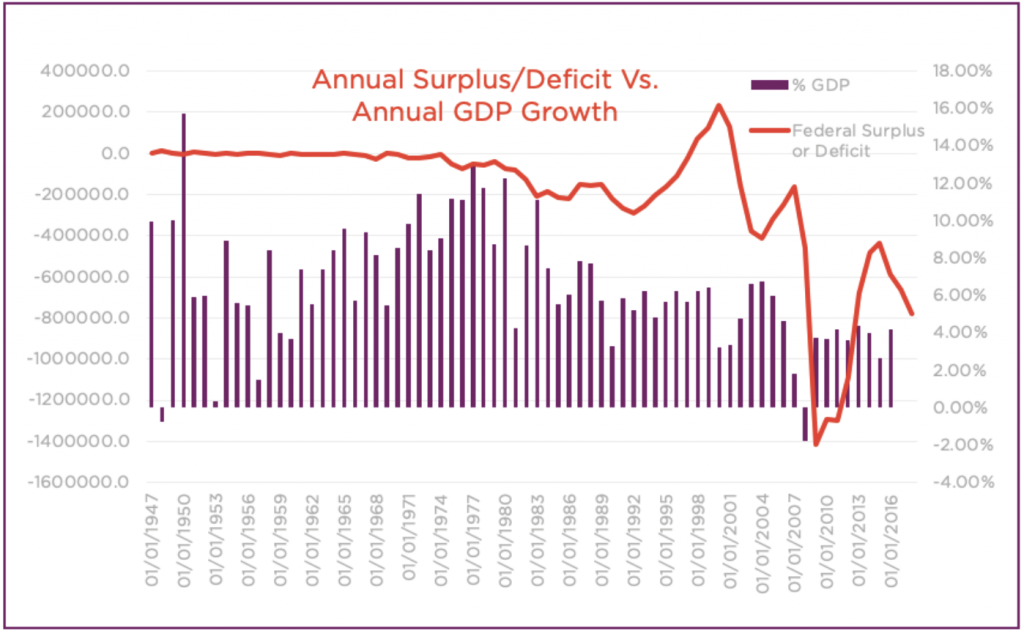

TREASURY BORROWING

The sharp increase in government borrowing could also push interest rates higher as the budget deficit is expected to top $1 trillion in 2019. The U.S. Congressional budget Office projects that by 2023, the interest on outstanding debt will be larger than the entire U.S. defense budget.

The U.S. Congressional Budget Office also estimates the US borrowing needs to be more than $12 trillion in the next decade. That’s $1.2 annually compared to $875 billion annually, during the last eight years where the economy was growing, if we enter a recession this amount will be much larger.

Source: FRED, Omnia Family Wealth

Growing deficits in a time where the economy is still strong and perhaps closer to the end of the economic expansion cycle is not a good sign.

CORPORATE DEBT LEVELS

Levels of corporate debt have exploded in the last 10 years thanks to record low interest rates. Debt levels, relative to GDP, exceeded the peak levels last seen in 2008. When zero interest rates are kept for a long time, the economy accumulates a massive amount of debt that is very sensitive to higher interest rates and could get to the point where these unprecedented amounts of debt eventually destabilize the US and global economy.

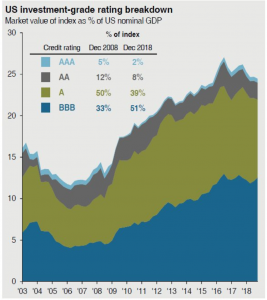

The chart to the right is another piece of the debt cycle puzzle. The portion of low-grade debt has increased dramatically in dollar terms and relative to GDP. BBB-rated debt, which is one notch higher then junk, is now 51% of the overall market, compared to 33% back in December 2008.

Source: FRED, Omnia Family Wealth

It’s important to note that, while corporate debt is higher in dollar terms than at the end of the last cycle in 2008, debt adjusted to cash flow (net debt) is still at mid-cycle levels. The part closer to the end of the cycle is in high yield debt.

HOW DOES A LONG-TERM DEBT CYCLE END?

History teaches us that long-term debt cycles end in either two ways, deflation or devaluation, and the government usually has to decide on the path. It’s a difficult decision to either let the economy collapse or for the currency to significantly devalue. Deflation will hurt workers, businesses and borrowers; currency devaluation will hurt savers and investors.

The points presented here suggest we could potentially be at the beginning of the end of a long-term debt cycle, and while we do not know when and through which scenario the cycle will end, we understand the magnitude and implications of each. The monetary system around the world has changed materially in the last decade and is now possibly wrong and broken, and we are certain to see additional changes as the system is being challenged not only by the economy but also by some major players.

We are not the only ones seeing this picture. Central banks are starting to be aware of the problem and will do everything they can to postpone the end of the cycle. That’s one of the reasons we wouldn’t be surprised to see a return of the QE policy as central banks realize the magnitude of the alternative.

In the chart below, markets already telling central banks the path they should follow.

Source: Bloomberg

Portfolio positioning is crucial at this point in the debt cycle, as many of the basic assumption of portfolio building investors rely on will be a challenge. Investors will have to rethink their core concepts of risk management, as it’s the only way to help them avoid major losses and be positioned to take advantage of major dislocations in the credit and equity markets.

“There were essentially only two ways to restore the past balance between the value of gold reserves and the total money supply. One was to put the whole process of inflation into reverse and deflate the monetary bubble by actually contracting the amount of currency in circulation. This was the path of redemption. But it was painful. For it inescapably involved a period of dramatically tight credit and high interest rates, a move that was almost bound to lead to recession and unemployment, at least until prices were forced down.

The alternative was to accept that past mistakes were now irreversible and reestablish monetary balance with a sweep of a pen by reducing the value of the domestic currency in terms of gold- in other words, formally devalue the currency.”

– Liaquat Ahamed, The Bankers Who Broke the World; p-156 (Central banks dilemma after WWI)

To download the full commentary, click here.

LEGAL DISCLOSURES

Omnia Family Wealth, LLC is a registered investment advisor with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. The information provided is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice and it should not be relied on as such. It should not be considered a solicitation to buy or an offer to sell a security. All information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. The views expressed in this commentary are subject to change based on market and other conditions. These documents may contain certain statements that may be deemed forward?looking statements. Please note that any such statements are not guarantees of any future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those projected. Past performance is not indicative of future results.