Monetary Shenanigans: Credit, Collateral and the Banking System

The U.S. Treasury market has delivered unexpected twists and turns over the past few months, keeping even the most experienced investors on their toes.

The Treasury market is traditionally considered dull and uneventful, and for good reason—it often is. Recently, however, the Treasury market has taken center stage with a surge of volatility reminiscent of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. The yield on the 2-year Treasury bond has shifted in ways we haven’t seen in at least three decades.

Here are four notable examples illustrating the magnitude of these shifts:

- In February, the yield curve—as measured by the spread between the 2-year and 10-year Treasury bond yields—inverted to a level not seen since the 1980s.

- Early March witnessed the largest two-day decline in the 2-year Treasury yield since the aftermath of the 1987 stock crash, as investors flocked to U.S. government bonds in the wake of regional bank uncertainty.

- An interesting anomaly emerged in April when the yield on the 4-week Treasury bill surpassed the rate in the Fed’s reverse repo program (this has since changed due to the debt ceiling issue, which I will explain below).

- On April 11, the interest rate swap spread for the 5-year period fell by 12 basis points, a significant drop. This decline brought the spread to its lowest level since the repo market crisis of 2019, and in fact, it even turned negative.

Negative interest rate swap spreads are counterintuitive—they occur when the fixed rate on a swap contract is lower than the yield on the corresponding maturity government bond. The fact that we saw them this year provides valuable clues about the underlying dynamics at play.

The phenomenon of negative interest rate swaps is primarily driven by dealers’ balance sheet capacity constraints. As the tightening cycle began and the yield curve inverted, investors like mutual funds, hedge funds, and foreign insurance companies reduced their holdings of longer-term Treasury bonds, anticipating lower returns. Consequently, dealers’ holdings increased as they absorbed the changes in supply and demand, resulting in balance sheet constraints. This imbalance heightened demand for swaps as a hedge against Treasurys, which in turn led to increased volatility and reduced liquidity in longer-dated Treasurys.

A contrasting trend appears on the other end of the curve. The yield on 4-week Treasury bills has fallen below the Fed’s Reverse Repurchase Program (RRP or repo) rate. The RRP, designed to help manage money supply and rates, allows financial institutions to deposit their reserves at the Fed to earn the program’s interest rate. When the RRP rate surpasses the rate on Treasury bills, this indicates that institutions are actively seeking secure collateral and choosing to invest in lower-yielding Treasurys instead of earning higher interest rates on their deposits. On April 24th, the RRP rate stood at 4.8%, while the yield on 4-week T-bills was 3.44%.

This situation indicates that dealers are becoming increasingly reluctant to accept other types of assets as collateral, leading to higher demand for short-term Treasurys. This development presents a larger problem, especially during market distress when the requirements and acceptability of collateral become more stringent. Dealers appear to be concerned about the quality and value of collateral, as well as counterparty risk, particularly in commercial real estate-related collateral.

As of June, the memo must acknowledge that the previous concern about debt default risk is no longer an issue. It’s worth noting that the RRP (Reverse Repurchase) rate is currently lower than the 4-week Treasury bill rates, but I believe this situation is temporary and primarily attributed to the recent debt ceiling drama. Money market funds, which are major buyers of short-term paper, have expressed apprehension about a potential “technical default,” leading to delayed payments on their bills. Such an outcome could result in the funds’ value dropping below the stable $1 per share mark, which could have severe repercussions.

The Credit-Collateral Relationship

Collateral plays a crucial role in supporting the function and liquidity of our financial system. During periods of uncertainty, demand for high-quality collateral increases, while its availability decreases. This imbalance puts additional strain on markets and creates instability. But the real trouble begins when collateral is liquidated, leading to a contraction in available credit.

Credit, one of the most vital factors in assessing the economic outlook, typically leads the overall economy and drives the boom and bust cycles. When markets are healthy, higher asset values reduce collateral constraints, making it easier for companies to secure more credit, make more investments, and stimulate economic activity. Investment activity contributes to higher asset values, which creates a positive feedback loop between collateral and available credit. In this sense, it is crucial to recognize the significance of commercial real estate collateral in facilitating credit.

Market liquidity is often measured through volume and bid-ask spreads, but the real essence of liquidity lies in the credit that is available and driving our financial system. In the economy, where financial activities play a dominant role, the refinancing function takes precedence over the creation of new money due to the substantial size of the debt. This pool of capital acts as the driving force behind our economic growth.

The credit-collateral relationship is a fundamental aspect of today’s economy. The availability of credit relies on the presence of sufficient collateral, while the value of collateral, in turn, depends on the availability of credit. New loans create new collateral, enabling the cycle of credit to continue. These loans are then invested in productive projects that fuel economic growth. Conversely, a drop in collateral values depresses the economy, as it reduces the number of new loans that can be generated for growth.

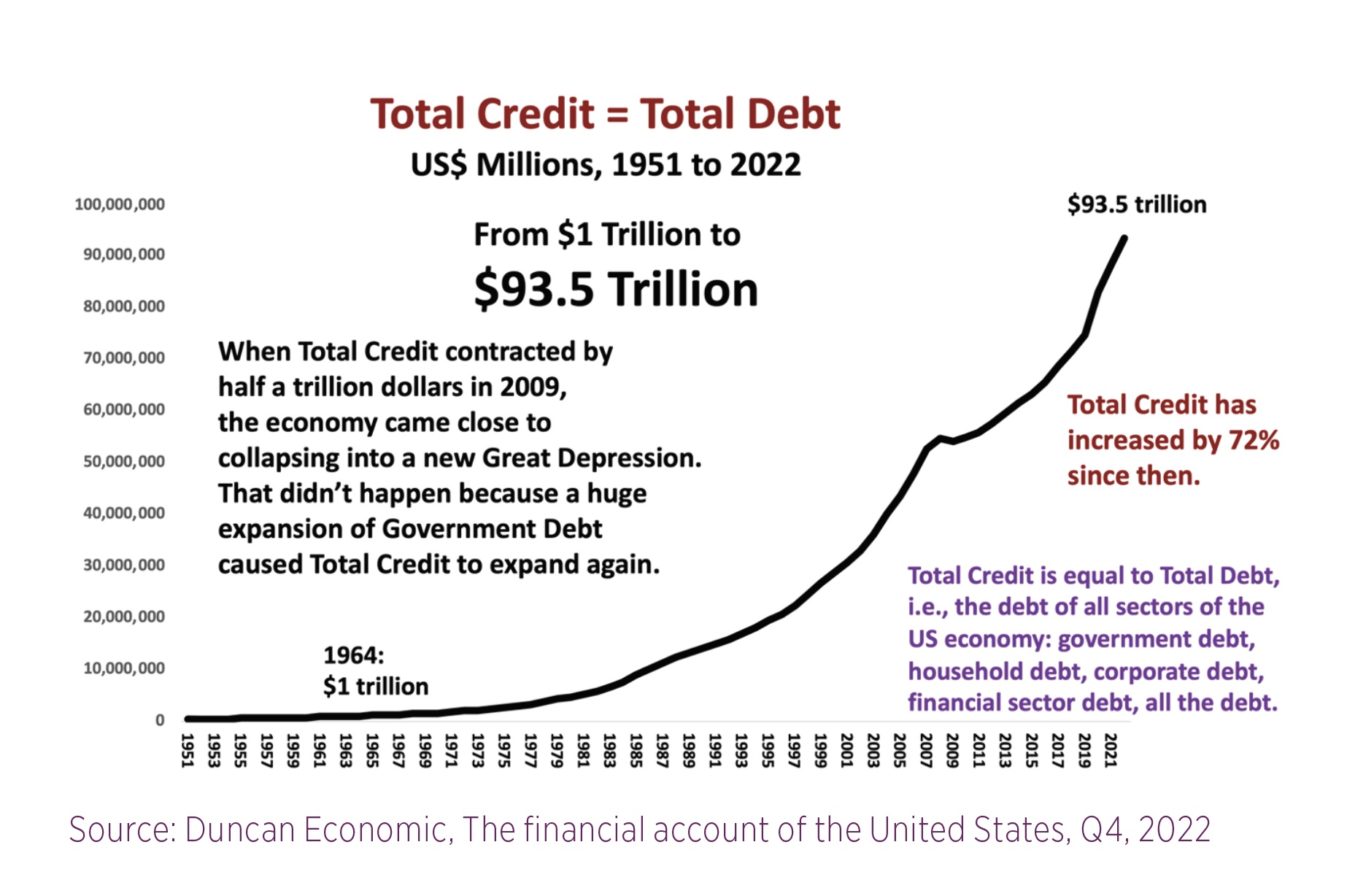

Unfortunately, the amount of debt has reached unsustainable levels in many Western countries, and credit growth is unable to match the pace needed for robust economic expansion (without central bank intervention). This imbalance can lead to an economic contraction and a subsequent decline in collateral values. Stimulation of the economy through the injection of new money and credit becomes essential to support collateral values.

As debt continues to accumulate, an increasing amount of money is needed to meet the obligations associated with servicing that debt. Consequently, there is less money available for making productive investments. This reduction in investments further diminishes the demand for loans. In a boom and bust cycle, the larger the size of credit and collateral, the greater the potential for a significant downturn. As depicted in the chart below, the amount of credit has experienced exponential growth in recent years.

A key question here is: how do these developments impact banks, which play the most critical role in our financial system, surpassing even the influence of the Federal Reserve?

While some investors believe the Fed possesses unlimited power to “print money,” the reality is that such actions rely heavily on the cooperation of the banking system. That’s why the stability of the banking system is of paramount concern, commanding our utmost attention.

Currently, our focus has shifted from deposit-related issues to the precarious state of banks’ balance sheets and the quality of their loan portfolios. One of the primary risks faced by most banks is what I refer to as the “loans pyramid.” In this process, the interest generated from one loan is utilized to secure another, creating the appearance of safe collateral for new loans. However, this approach also introduces systemic risk into the financial system. It is crucial to note that this type of collateral is considerably weaker and more susceptible to distress compared to assets like Treasurys. While banks can now post their underwater Treasury with the Fed, akin to a remedy for the “SVB (Silicon Valley Bank) flu,” and obtain funds at par, this approach fails to address the fundamental collateral problem.

History has shown that financial crises often stem from refinancing and funding challenges.

Looking and Thinking Ahead

In the years ahead, a substantial volume of refinancing needs to be undertaken, and it will come at a significantly higher cost. This impending task presents a pressing concern within the financial landscape, requiring effective strategies to mitigate associated risks and to ensure the sustainability of the banking system. I must express my doubt that regulators or the Fed fully comprehend these strategies.

In conclusion, the recent monetary shenanigans and the presence of inverted yield curves are clear signs that something troubling is unfolding. These issues are not distant future risks, but immediate concerns demanding our attention. While the curves remain uncertain about when we might see lower interest rates, once they do, the decline is expected to be significant. As time passes without a recession or corrective measures to address weak credit and collateral, the vulnerability of our banking system to weak collateral intensifies. Central banks continue to postpone a financial bust by expanding credit, but this approach always brings unintended consequences. The inherent instability of our financial system, with its reliance on credit and the credit-collateral loop, becomes increasingly apparent.

It is important to acknowledge that this is not just a problem limited to the United States. It is a global challenge. Yield curve inversions extend beyond the U.S., with the German curve also exhibiting this phenomenon—a rarity in this market. We observe similar hedging activities in different countries and currencies, reflecting the scale of these challenges.

Moreover, the balance sheet constraints faced by dealers can ripple throughout the banking system due to their interconnectedness and the potential for contagion. Dealers, known as market makers, play a crucial role in facilitating trading and liquidity across various financial markets, including bonds, equities, and derivatives. When dealers’ balance sheets come under strain due to market volatility, deteriorating credit conditions, or adverse economic events, their ability to maintain sufficient capital, liquidity, and risk-bearing capacity is compromised. Such constraints have several potential implications for the banking system at-large.

While navigating the intricate world of investing, we must remain vigilant and prepared for the risks and opportunities that lie beneath the surface. During times of crisis, opportunities emerge, and it becomes our responsibility to position ourselves strategically to capitalize on them.

It’s worth mentioning that, while many advisors may overlook the intricacies beneath the surface of markets, we firmly believe in the importance of diving deeper. The Treasury market is a major part of the plumbing in our financial system, and it holds valuable insights we need to monitor closely. By understanding the dynamics at play in this critical market, we can navigate the complexities of the financial landscape with greater clarity and make well-informed investment decisions.