Inflation or Deflation and the Transition Mechanism

For the last several years, advisors and economists have been complaining about the massive money printing by the Fed and predicting an inflationary explosion. These voices are much louder today, and advisors continue to caution “inflation is coming” to investors because it is often assumed that Fed money printing = inflation. But is it commonly known what money-printing actually is? And how does money printing turn into inflation? I suspect most people do not.

The Fed is not printing money

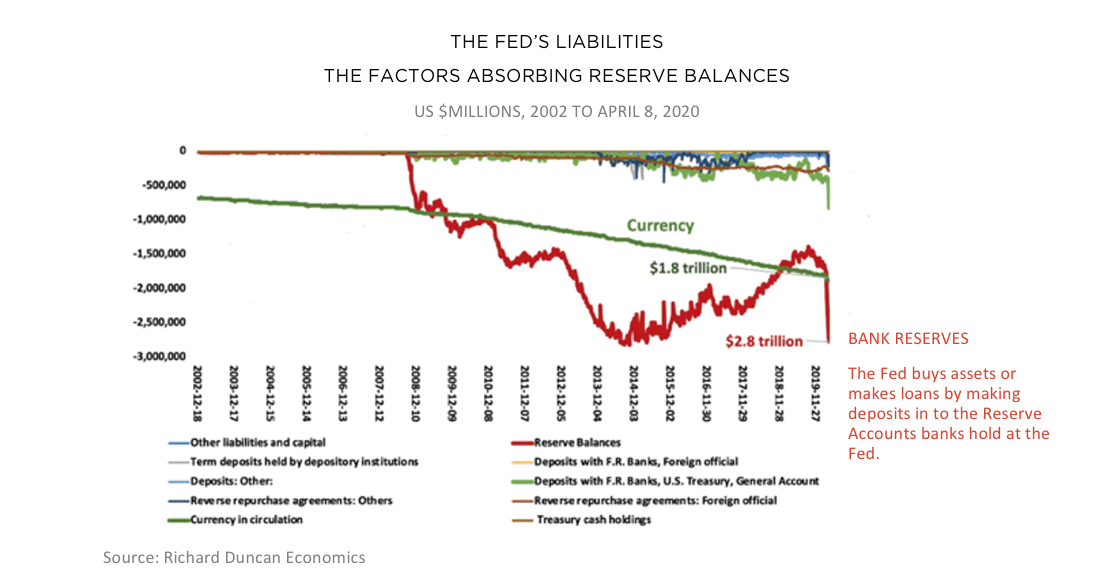

The only thing the Fed is creating is bank reserves, not actual money, by depositing money in a bank account the commercial banks hold at the Fed. The Fed makes these deposits when they want to add liquidity to the banking system to avoid a crisis or to help banks make new loans, as they do now. The reserves are not considered credit and do not follow through to the actual economy without the banking system pushing them, and to this point, the banks have not done this in an impactful way.

However, regardless of how much the Fed encourages the banks to take additional risk and make additional loans, bank balance sheets do not allow them to. In 2008, the large banks leveraged their balance sheets, and we all remember what the consequences were. In fact, during the crisis, the Fed and Treasury actually “asked” banks to take over other failing banks, expanding their balance sheets massively, which was largely unpopular with Washington and the public when the crisis ended.Since then, banks have been faced with a myriad of restricting regulations (Basel III, Dodd Frank, BIS, FOMC and others) to make sure the financial crisis doesn’t happen again. That has restricted the banks’ capacity for risk significantly. This was clearly demonstrated in September 2019 when repo rates suddenly increased to 10%, and the repo market basically stopped functioning. In addition, the Fed’s policy rate (the fed funds rate) jumped above its target range. Banks, who are the main dealers in this market, stopped taking collateral from other entities because their balance sheets couldn’t afford it. At that point, the Fed had to step in, injecting the needed liquidity by taking the collateral that the banks couldn’t take without help.

But that was a temporary fix.

It’s also important to remember that commercial banks are already struggling to make profits with a flattening yield curve and term structure, so there is less incentive to take additional risk. This is demonstrated in their depressed stock performance.

The next chart shows the growth and contraction of bank reserves through 2008, growing during QE, contracting during QT and since March 2020 growing again to record size.

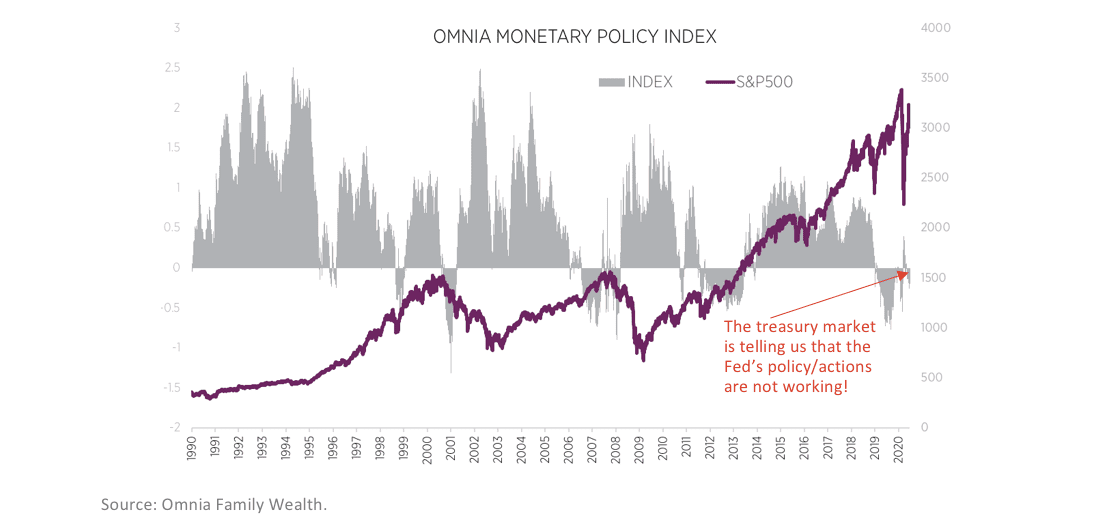

Different durations on the yield curve mean different things, and looking at how they behave independently and then in relation to each other can tell us a lot about the condition of the economy and monetary policy. It’s also important to look at the way a curve got to its current shape. In the chart above, our index translates what the treasury market is telling us (across durations): no recovery.

The same problem in Europe

Recent action taken by the ECB provides additional evidence that this is a problem.

In September, the ECB announced a new policy to help banks make loans by lowering the leverage ratio that is required of banks to maintain. The ECB allows the banks to exclude the deposits they make at these banks from the leverage ratio calculation, so they have more money to make new loans. It is similar to the action taken by the Fed in 2008, but in a different way.

Still plugging a hole

We must remember that a significant amount of the money the Fed is trying to create is replacing money that was “destroyed” since March from bankruptcies of corporations, loss of value in portfolios and loss of jobs/income. This is money/credit that is no longer part of the system. We wrote about this problem most recently in June 2020 where we focused on debt issuance and liquidity. Much of the increase in the Fed’s balance sheet goes to repaying maturing debt and buying new debt/treasuries to fund the government’s fiscal stimulus and other types of debt to allow corporations and the fixed income market to continue functioning. That’s also the reason we do not expect the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) funds to be inflationary; they are only replacing consumer buying power that was lost.

“New” Fed Policy

More evidence we have that there is no inflation is the major change in the Fed’s policy to let inflation “overshoot,” which they announced at their last meeting:

The Fed’s objective is to manage expectations, hoping this will quell investors’ fears. This “new” policy isn’t new at all, it has been the bank of Japan’s policy for years. This policy does not make sense, in my opinion – even though the Fed has not been able to achieve its 2% inflation target, Powell assumes that by saying he will allow inflation to “overshoot,” this will lead to higher inflation.

Where do we see inflation?

We do see inflation in one main area: financial assets. First, zero percent interest rates for a prolonged period of time pushes savers and investors to look for yield and return in riskier assets and inflates valuations significantly. As an example, examine the recent craziness in “SPACs.” Second, as investors fear the actions of the Fed and government will eventually hurt the US Dollar, they hedge themselves with financial and real assets to preserve their buying power.

Why can’t we get away from these consistent deflationary forces?

The primary driver for the deflationary environment in which we have been for the last 12 years, and likely will remain in for a while, is the amount of debt we have accumulated, at the federal level and at the corporate and consumer levels. At some point, too much debt hurts growth and becomes deflationary as debt servicing costs become a weight on earnings and growth, and the only way to sustain it is through lower interest rates. That’s where we are today, and without a change in the debt load, there will be no change in the deflationary pressures.

As we wrote in 2018 about the long term debt cycle, there are only two solutions for this problem: deflation or inflation, meaning default on the debt or devaluation of the currency. Governments throughout history have chosen the pain of devaluing the currency, unless it was not possible (the currency already crashed), with a default on the debt as the only option.

What should the Fed and government do?

Remember, there’s no relationship between reserves and inflation. Reserves become printed money once they flow into the economy through bank loans, which then can be inflationary. But while the Fed is focusing on helping banks make new loans, it cannot influence the demand for these loans from the private sector and loans that would support economic growth. At this point in time and mostly due to the crisis, fiscal policy monetized by monetary policy is the only solution, we need to find a way to bypass the banking system until that problem is resolved. But that is a temporary solution as well.

A final point to remember

Over leverage and indebtedness causes these two problems: the borrowers can’t borrow any longer, and the lenders can’t lend any longer. Unfortunately, I do not see a healing process without a painful “reset.” Japan has avoided a reset for 30 years, preventing normal debt cycles to take place and balance the system. The price they pay is too high. Even if we do not choose to reset, the markets eventually will do it for us, even if it takes years.

At this point the possibility of the world resolving its debt problems through growth is not possible. In the process of resetting our financial system, we will need to let go of excess capacity (that also means to allow large companies to default) in many industries and invest heavily in new growth industries.

It is critically important for advisors and investors to understand the macro picture. The risks in the public equity and fixed income markets are significant, and expected returns have collapsed. The vast majority of portfolios are invested in these two markets, which means they take all the risk for minimal expected returns. It is time to adjust your investment methodology and take these issues into consideration.

Click here to download the article.

Important Information

Omnia Family Wealth, LLC (“Omnia”), a multi-family office, is a registered investment advisor with the SEC. This commentary is provided for educational and informational purposes only. It does not take into account any investor’s particular investment objectives, strategies, tax status, or investment horizon. No portion of any statement included herein is to be construed as a solicitation to the rendering of personalized investment advice nor an offer to buy or sell a security through this communication. Consult with an accountant or attorney regarding individual tax or legal advice.

Advisory services are only offered to clients or prospective clients where Omnia Family Wealth and its representatives are properly licensed or exempt from licensure. Information in this message is for the intended recipient[s] only. Please visit our website https://omniawealth.com for important disclosures.

This content is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended as a recommendation to invest in any particular asset class or strategy or as a promise of future performance. References to future returns are not promises or even estimates of actual returns a client portfolio may achieve.

The views expressed herein are the view of Omnia only through the date of this report and are subject to change based on market or other conditions. All information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. Omnia has not conducted an independent verification of the data. The information herein may include inaccuracies or typographical errors. Due to various factors, including the inherent possibility of human or mechanical error, the accuracy, completeness, timeliness and correct sequencing of such information and the results obtained from its use are not guaranteed by Omnia. No representation, warranty, or undertaking, express or implied, is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information or opinions contained in this report. This report is not an advertisement. It is being distributed for informational and discussion purposes only. Omnia shall not be responsible for investment decisions, damages, or other losses resulting from the use of the information. This report is not intended for public use or distribution. The information contained herein is confidential commercial or financial information, the disclosure of which would cause substantial competitive harm to you, Omnia, or the person or entity from whom the information was obtained, and may not be disclosed except as required by applicable law.

Statements that are non-factual in nature, including opinions, projections, and estimates, assume certain economic conditions and industry developments and constitute only current opinions that are subject to change without notice. Further, all information, including opinions and facts expressed herein are current as of the date appearing in this report and is subject to change without notice. Unless otherwise indicated, dates indicated by the name of a month and a year are the end of the month.